A Map of Longing

Greetings Friends and Neighbors,

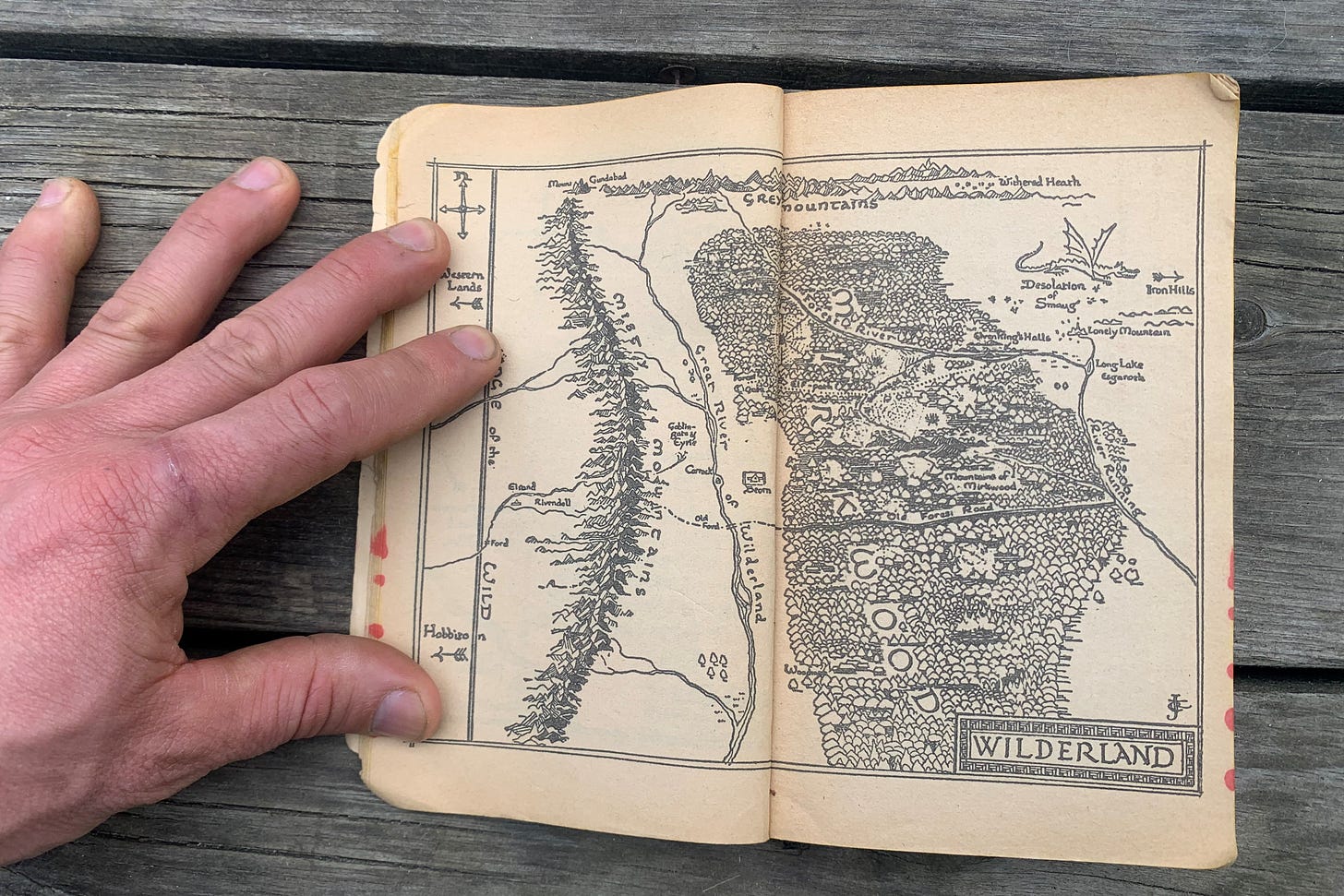

I am writing a book that tells a story of giving food away at Brush Brook Community Farm. While that Farm project has been closed for a year and a half now, the website is still live. The home page reads: “Brush Brook Community Farm is an experimental agricultural gift economy in Huntington, Vermont.” As I write, I am realizing that the book amounts to a map—story lines scratched onto a blank page to summarize a living terrain peopled by humans and nonhumans. Maps are used primarily for navigation, for wayfinding. We rely on navigation in every moment as we decide which way to proceed—right, left, forward. Where to procure food, to find love or companionship, to seek rest, to alleviate boredom. But we don’t tend to use maps for terrain with which we are familiar. It might seem an obvious statement, but let it sink in for a moment.

I recently talked with a class of college students about the late Brush Brook Community Farm. I began by asking them to raise their hands if they knew what “community service” was. All hands went up. “How many of you have done community service?” Again, all hands. “Would anyone be willing to offer an example?” A volley of one-sentence stories filled the air. “I raked leaves once for my elderly neighbor.” “I volunteered for a few hours at the Food Pantry.” “I picked up trash on Earth Day.”

Then I asked, “If the phrase community service describes a unique terrain of interaction that exists over here, what words would you use to describe the rest of the terrain? The patterns of interaction that make up the rest of our lives?”

A long silence. Tentatively, one of the students said, “Making money?” More silence. And then, from behind my right shoulder, the professor said, with an uncertain, even confessional tone, “Self-service?”

My first question asked a what question. As in, “What did you do that would be called community service?”

But a map and a navigational program are not the same thing. I don’t have a smartphone, so perhaps this assertion betrays my backward-facing orientation.

In retrospect, I could have asked some follow-up questions:

How did these college students decide to leave their familiar terrain of interaction and take a journey through the distinct and distant landscape we call community service?

Why, after a few hours there, did they return to the more-familiar patterns we call the rest of our lives?

Asking How and Why requires us to consider human motivation. These are questions that inquire about our wayfinding practices.

When I was in college, an anthropology professor tried to illustrate the meaning of the word culture. He said, “Have you ever wondered why we dim the lights before we sit down to enjoy a fancy meal? Wouldn’t we want to see the food clearly?” His point was that our own cultural norms are mostly unquestioned, and will therefore remain invisible to us.

Brush Brook Community Farm began by drawing an imaginal boundary around one small patch of ground on occupied, unceded Abenaki territory in a narrow mountain Valley in present-day Vermont. The boundary was articulated this way: Nothing from this place will be sold. All of the food grown here will instead be offered as a gift to anyone who is hungry for any reason. Absent our habituated modes of market transaction, what other patterns would we learn instead? How would we ask to be sustained? We had no map of the terrain we would try to traverse, no proposed route of travel. We had hearts full of longing instead.

If a map allows us to imagine venturing into unfamiliar terrain, then the book will necessarily address the question of what we did at Brush Brook Community Farm—the breeds of cattle and sheep we grazed, the arrangements we made with landowners, the number of quarts of soup and loaves of bread we distributed, our monthly budget requests. Think of the college student’s statement, “I picked up trash on Earth Day.”

But Why did we feel the need to draw a boundary around a portion of the terrain and give it a specific name—to differentiate it? How did we figure out what to do each day? These are questions of motivation and wayfinding. Sending a book about Brush Brook Community Farm into the world will amount to extending my hand and inviting strangers to walk with me into unfamiliar terrain. And so it seems incumbent upon me to try to put words to the unquestioned and unnamed rest of our lives. To attempt to shine some light on the invisible maps in our minds. To try to describe the familiar terrain from which the name Brush Brook Community Farm emerged.

The title of the college class I spoke with the other day: Religion and Social Justice. The students asked me a lot of How questions about Brush Brook. They wondered how they might proceed in a world where much of what I was describing seemed impossible, even fantastical. They were asking me for a map. I wasn’t sure I had one for them, at least not one that came with a pre-installed navigational program. But as I listened to their earnest questions I caught a glimpse of the world as seen from their seats. They already had maps they were working from, and wayfinding strategies. Sure, some of those maps and strategies might be described by the terms “making money” and “self service.” But I began to see something that more closely resembled a navigational program. I’m going to call it a map of longing—for that which seems to be out of reach. And perhaps my telling them a bit of the Brush Brook story allowed that map of longing to become visible for a moment.

If that is the consequence of the book being in the world—that our longings are given permission to come out from hiding and even to find voice and begin to offer us guidance through uncharted and dangerous terrain—I will be glad to have poured my labors into it.

Many thanks to you for reading.

With great care,

Adam