Greetings Neighbors and Strangers,

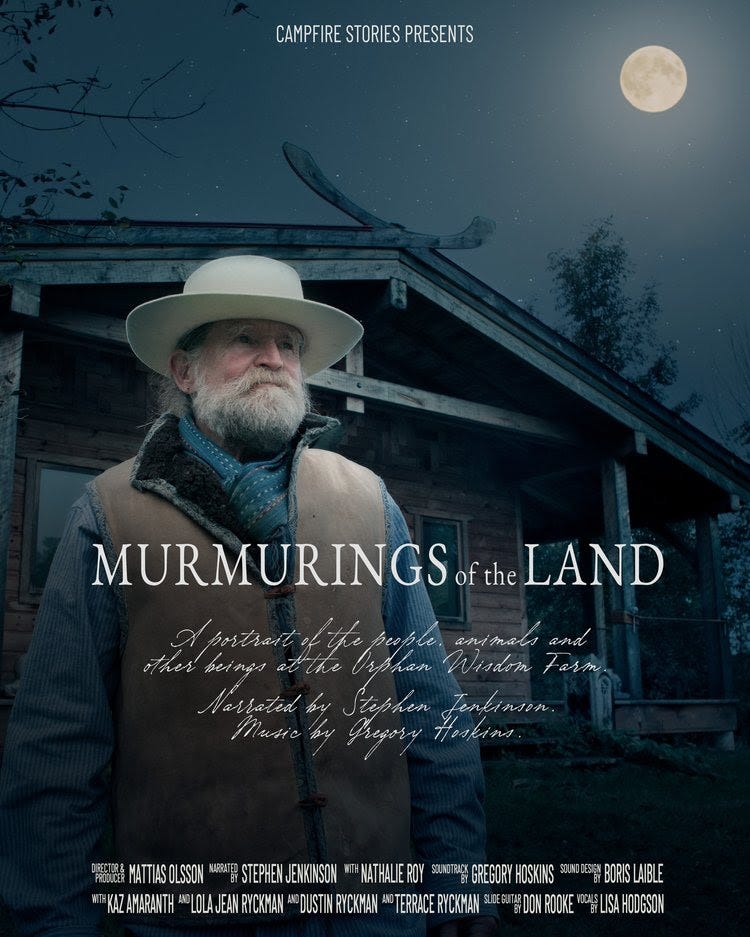

Before sharing this morning’s writing, I encourage you to take a look at an exquisite short film by Mattias Olsson, called Murmurings of the Land with farmer/culture worker Stephen Jenkinson.

Mattias has charted a path toward practicing the culture work as described in the newsletter story below—simply replace my ‘farmer’ with his ‘storyteller.’ Mattias found that he couldn’t make the films most needed in our time by first pitching them to funders. Instead he asks all of us for sustenance.

Farmer as Shaman.

Originally published in 1997, David Abram’s Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, offers to re-acquaint Western readers with the creaturely sense(s) they haven’t yet completely outgrown. It can be unsettling to learn that you still have the requisite sense, or senses, to form mutually sustaining relationships with your human and nonhuman neighbors.

I must have listened to the audiobook seven or eight times through. One section in particular caught my attention and guided my neighborly farming adventures in the early going.

As a practicing sleight-of-hand magician, David Abram developed a hunch that magic serves an essential cultural function. He traveled to Indonesia and Nepal on a grant to study the relationship between magic and medicine. To his surprise, the magicians he met there—to whom he refers interchangeably as shamans, sorcerers and medicine men/women—studied their craft through daily, diligent attention to nonhuman life. Their capacity to provide healing services—say, to extract a malevolent spirit from an afflicted human—arose from their ability to heal the relationship between the villagers and the surrounding landscapes upon whom they relied for food, clothing and shelter.

From within the modern world I inhabited, the shaman David described sounded a whole lot like the first-generation farmers I knew; or, at least I recognized in his description of the shaman’s cultural function the longings that had turned my young farmer friends away from the grocery store future they’d been taught in school and back toward the living land. As I listened to David’s story, my mind began making the word substitution, from ‘traditional shaman’ to ‘ecological farmer.’

The [farmer]...acts as an intermediary between the human community and the larger ecological field, ensuring that there is an appropriate flow of nourishment, not just from the landscape to the human inhabitants, but from the human community back to the local earth.

The movement for sustainable agriculture began as a great, orgasmic, act of falling-back-in-love, with an Earth that grows human hearts and tongues, lips and lungs, songs and stories. The local food movement aimed to plant the human story back into the Earth as food for that hallowed home ground.

By [the farmer’s] constant rituals, trances, ecstasies, and ‘journeys,’ he ensures that the relation between the human society and the larger society of beings is balanced and reciprocal, and that the village never takes more from the living land than it returns to it—not just materially, but with prayers, propitiations and praise.

Let’s replace “rituals, trances, ecstasies and journeys” with “love affair.” We push our attention and care toward the one(s) with whom we have fallen in love.

The farmer I began to imagine as I listened isn’t a Green Peace activist. She isn’t chained to a tree before a line of approaching dozers. She isn’t here to protect the Earth from humans, but rather to protect her human neighbors from the danger of isolation—the danger of ‘becoming like an island.’ This farmer is madly in love with an Earth that is still madly in love with humans, and so her love affair is not species-specific. Humans must eat in order to sing, dance and pray, and the Earth this farmer loves still longs to hear the sound of human conviviality. Humans must receive the gift of food in order to become deep practitioners of gratitude.

The farmer I imagined labors on behalf of humans and the Earth simultaneously by sensing how much the landscape can sustain, by learning how to identify ‘too much,’ and then translating those limits into human language and lifeways. This farmer is a healer of relationships.

And it is only as a result of her continual engagement with the animate powers that dwell beyond the human community that the [farmer]....is able to alleviate many individual illnesses that arise within the community. The [farmer]....derives her ability to cure ailments from her more continuous practice of “healing” or balancing the community’s relation to the surrounding land.

When this farmer/magician/medicine woman delivers supper to the village square, the townspeople beg her to let them know how they could more deeply sustain and encourage her work. They wonder whether they might learn some of his magic ways. They ask her for guidance on the appropriate portion size. They ask him to help them figure out how to live.

To some extent every adult in the community [was]....engaged in this process of listening and attuning to the other presences that surround and influence daily life. But the [farmer was]....the exemplary voyager in the intermediate realm between the human and more-than-human worlds, the primary strategist and negotiator with the Others.

Clearly, we don’t cultivate farmers—or community members—of this kind today. The tight grasp of the market pushes them away from the work of attunement at an alarming rate. Rising land values and falling commodity food prices convince many young people to give up on the dream before they can even begin. And yet I’ve met hundreds of people with these endangered relational sensitivities. Humans who can’t keep themselves from falling in love with the Earth are the cultural canaries in the coal mine. We need many millions more of them today.

Western industrial society, of course, with its massive scale and hugely centralized economy, can hardly be seen in relation to any particular landscape or ecosystem; the more-than-human ecology with which it is directly engaged is the biosphere itself. Sadly, our culture’s relation to the earthly biosphere can in no way be considered a reciprocal or balanced one: with thousands of acres of non-regenerating forests disappearing every hour, and hundreds of our fellow species becoming extinct as a result of our civilization’s excesses, we can hardly be surprised by the amount of epidemic illness in our culture, from increasingly severe immune dysfunctions and cancers, to widespread psychological distress, depression and ever more frequent suicides, to the accelerating number of household killings and mass murders committed for no apparent reason by otherwise coherent individuals.

In order to stay in healthy working order, a culture needs farmers who are being trained and encouraged to serve as agents of cultural repair. The responsibility for maintaining those farmer/culture workers falls not upon the market, the state, or the charity complex. It falls upon their non-farming neighbors, the ones who eat food in order to stay alive. The same ones who allowed themselves to be seduced into becoming consumers. The abandonment of that cultural responsibility will be borne by our heirs for generations to come. We could still decide to change course, even at this late hour.

With care, Adam

Hey Adam, I’m so happy to read this post this morning, as what you describe has been my life for the last nearly 7 years, in various stages of awareness, of course. I’ve been a student (thwasa) in the South African healing tradition of ubungoma, a very painful and oftentimes slow process, but the heart of becoming a traditional healer is becoming a facilitator of repairing and strengthening relationships, definitely not just among people, or the living. And among those lessons is learning what makes a healthy relationship, what is required to tend to those relationships? For most modern people, at least Americans, this is a deep unlearning, as many of us don’t have experience with truly healthy relationships.

In my growing awareness that traditional healers are “ecologists” or “systems thinkers” there is also the awareness that for people to adjust or even transform their inner worlds to be truly aligned with life and healthy relationships with all of life, the motivation just doesn’t stick around. The burn out and distraction/addictions are real, and another to-do list, even one built on doing the right thing, especially when it’s such a challenge to identity/ego and hopes and desires, like simplifying and living earth-aligned, yikes. There’s no sticking power there. Even my spiritual friends won’t talk with me about plants and animals beyond IG clips. Never mind any openness to the reality of faster and harder ecological collapse. What works is love. We take care of what and who we love, and it’s less of a chore, a to-do list. But even though there’s a deep longing for this in the collective, ideas like this are rarely touched. At least when I’ve lamely attempted to convey them. People desire, always. They desire love relationships and abundance. That’s easily fulfilled in an earth-aligned life, especially one guided by those wiser than us, human, other than, and the guiding Ancestors, from my own experience.

In Vedanta and yogic traditions, teachers say that in this Kali yuga, the path that makes the most sense is the Bhakti path, passionate love, devotion and surrender. Being a bhakta of nature in these times 👍

Thank you for sussing this out publicly. I don’t feel as awkward, weird, and uncool 🤣 the socials are just 8th grade all over again, ya know? Ps- I love Stephen Jenkinson. Cultural orphans need guidance to find their way back to family of life, and being people of place.

Hi Adam, I work at a small natural food store in suburbia and this article is so refreshing and spot on.

This quote in particular resonated with me: ‘The farmer I began to imagine as I listened isn’t a Green Peace activist. She isn’t chained to a tree before a line of approaching dozers. She isn’t here to protect the Earth from humans, but rather to protect her human neighbors from the danger of isolation—the danger of ‘becoming like an island.’ This farmer is madly in love with an Earth that is still madly in love with humans, and so her love affair is not species-specific. Humans must eat in order to sing, dance and pray, and the Earth this farmer loves still longs to hear the sound of human conviviality. Humans must receive the gift of food in order to become deep practitioners of gratitude.

The farmer I imagined labors on behalf of humans and the Earth simultaneously by sensing how much the landscape can sustain, by learning how to identify ‘too much,’ and then translating those limits into human language and lifeways. This farmer is a healer of relationships.’

My conservative elders think of all activists and people who are for sound environmental practices as the one chained to the tree and I’ve been working to educate otherwise.

Thank you.