Greetings Neighbors and Strangers,

The house is sheltered on three sides. White Pine and Cedar, curve of hill, even bare-twig Maple and Hickory slow the approach of North and West. South Wind, when she comes directly, must make her way through tall pines on the far side of the narrow field, as if squeezing through the bristled tines of a great comb, before dropping to house level. By the time she knocks on the door, she’s mostly huff and bluster. But this morning the bone shaker’s come to town. Open field to the Southeast allows powerful gusts to build, audibly, before buffeting the tall corner of the house. The pots just rattled on the stove. The pup lays in her bed with both eyes open, unsure whether to bark at this strange and noisy visitor. Sleep may prove elusive for both of us until the gale passes.

I find it easier to remember that the world is alive when there’s a wind on. In his fine book, Come of Age, Stephen Jenkinson suggests, “Alive means ‘of consequence.’ It means ‘it pushes, it pulls.’ It means the world is sentient.” I could make my statement other way around and it might prove more accurate. The arrival of house-rattling Wind this black morning grants me a break from my habit of forgetting that the world is alive. Alive “does not mean the world is benevolent, as in ‘tends to benefit or favour or bear me in mind because I mean well.’”

Windless, room-temperature air can be found every day inside of buildings but only very occasionally out-of-doors. While comfortable, I wonder if too much stillness may act like a sedative for human beings, leading to an underdiagnosed form of amnesia. A spell of lonely de-animation.

Wind pushes and pulls. Wind is definitely not benign. And yet without wind, and in particular this fearsome South Wind, we would find ourselves trapped in a perpetual winter here in the North Country. I call her Greening Wind for this reason. Winds oversee the turning of the seasons. They do not appear to benefit or favor us in our sleepless midnight moments spent wondering what’s being torn asunder around the Farm. But perhaps they do bear us in mind by offering to break us of our de-animating, lonely-making habits.

I heard a remarkable interview years ago with a Dakota poet named Layli Long Soldier. It’s quite a name she carries. The title of the show, “The Freedom of Real Apologies,” hints at the material she and Krista Tippet cover, including her collection of poems responding to the U.S. Government’s half-hearted and carefully-hidden apology to native people. In the interview she tells a story about a teaching she carries from her grandmother, who used to remind her and the other kids not to speak poorly of Cold or Wind. Out on the Dakota plains, I can only imagine the frequency with which such verbal displays of disapproval might seem appealing. “You must be very careful,” her grandmother said, “because they are always listening. They will bite you.” Perhaps our modern English term “frostbite” serves as a breadcrumb to a long-forgotten animistic awareness.

After listening to that interview, I decided to go cold turkey on complaining about the weather. I haven’t done it since. Abstinence has brought the practice into view as sort of national pastime. If you’re reading this newsletter from Europe or elsewhere, perhaps you can chime in as to whether it’s any different there. Breaking that habit of speech seems to have begun a slow process of loosening the spell of un-aliveness. I call it picking the language knot.

When I bump into someone at the post office or the hardware store, I search for grateful words to describe the arrival of discomforting weather patterns. If I can’t find grateful ones, I fall back on statements of awe and wonder. “The sheer power of Wind rattling the house tonight makes me feel small, a part of something vast, black, alive, and definitely not benign.” More alive might also mean less alone.

The world is alive. Alive means “of consequence.” It means “it pushes, it pulls.”

For Layli Long Soldier’s grandmother, it was of utmost importance to teach the children that they were also alive. Their actions and words pushed and pulled upon the world. She wanted the children to know that they mattered, that they were being listened to. That they were in fact never alone, even when no other humans stood nearby. Now that’s some medicine for our time.

I’m going to make a turn now that you might not expect, but it’s where I was headed all along. When Wind pulled me from slumber a few hours ago I had a story on my mind. I haven’t been able to shake it for a couple of weeks now as I chip away at a book about my adventures in food gifting, in which I wrote, “The gift as I’ve described it here can sound pretty dreamy and out of reach, a bit like walking through the back of the wardrobe.” The reference is, of course, to C. S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I will leave you with a bit of that story, which might serve as an invitation to see the gift as a re-animated commodity—a trickster and a spell-breaker at once. An opening into a world alert and alive, a world wherein humans are immensely consequential.

Lewis begins the story by introducing us to young Lucy, who, along with her three siblings, has been sent to a large house owned by a very old Professor way out in the country to wait out the London air raids. There was nothing Lucy liked so much as the smell and feel of fur. As such, she couldn’t keep herself from stepping through the open door of a wardrobe to rub her face against the fur coats hanging there. Reaching out a hand, she found not the back of the wardrobe but a second row of coats. The sensuous wardrobe quickly enveloped young Lucy.

Instead of feeling the hard, smooth wood of the floor of the wardrobe, she felt something soft and powdery and extremely cold. “This is very queer,” she said, and went on a step or two further. Next moment she found that what was rubbing against her face and hands was no longer soft fur but something hard and rough and even prickly. “Why, it is just like branches of trees!” exclaimed Lucy….A moment later she found she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

I remember listening, rapt, as my mother read aloud to me a tale of a magical land full of talking animals. The first one Lucy encountered, a Faun named Tumnus, began the conversation by confirming that she was indeed what he suspected.

“You are in fact Human?” asked the Faun.

“Of course I’m Human,” she replied, puzzled.

Lucy explained to Mr. Tumnus how she’d found him there in the woods by stepping through the back of a wardrobe in a spare room within a very large house.

“Ah!” said Mr. Tumnus in a rather melancholy voice, “if I had worked harder at geography when I was a little Faun, I would no doubt know all about those strange countries. It is too late now.”

“But they aren’t countries at all,” said Lucy, almost laughing. “It’s only just back there—at least—I’m not sure.”

I can’t help but think of Layli Long Soldier’s grandmother this morning as I read the final pages of Lucy’s adventure. She and her siblings, in an effort to explain to the old Professor why four fur coats from his wardrobe have gone missing, tell him what they’ve seen and done there in the animate Other World called Narnia. To their great surprise, he believes every word of their story.

I will leave it there for now. I send you dark, windswept and oddly-warm year-end greetings from the Farm. May you find occasion to remember your carnal aliveness before long. More alive might mean more consequential and also less alone.

With love,

Adam

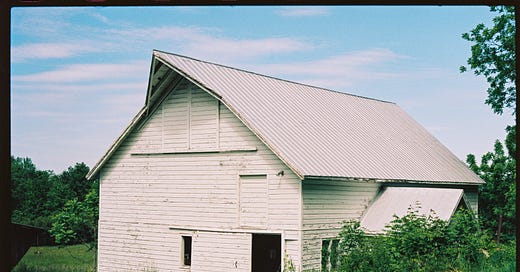

I’m still living (for only a week more) in the house I grew up in. She has sheltered us from many a howler, and we have loved her well. The trees on the back hill have grown so that their nearest branches brush the house, and are just outside my bedroom window, clinging precariously above the brook, so that it feels (especially in a wind storm—when the Norway spruces and sugar maples sing and wail, and the wee brook roars) like I’m living in a tree house.

“Tree at my window, Window Tree…” (oh please read Robert Frost’s beauty of a poem, you won’t regret it.)

In this snug although old and creaky house, I’m grateful for the exhilaration of a storm, and grateful when it’s over. For she which the old ones built and loved has sheltered my family these 65 years. I will miss this old home. I’ll miss the many sounds of the brook, and the leaf or bare branch wind songs. A thousand thank-yous Adam for your post of awe and appreciation which brought me fully into my heart, and brought the animate world outside my window into my heart upon my awakening this rain-speckled morning. Grounding kinship which inspires wonder is such a gift.

Well, Adam, I can confirm that the human denizens of this pocket of rural Flanders most certainly do complain about the weather (although not usually in English)!

Bless you for evoking Narnia. I experience my home (the house, at least) as playing the role of the back of the wardrobe. I step it from the street and traverse two rooms to exit out the other side into an overwhelmingly alive and communicative other reality, properly called the 'Earth', as opposed to 'the world' which lies street-side ...